I'm a doctor! (ish)

Since last June, a lot of things happened. I finished my PhD and passed my viva! I'm now a doctor!

That is, of the PhD kind. I'm still working on becoming a doctor of the medical kind, and I have one-and-a-half years left of Clinical School at Cambridge. I had a grant total of one day off between submitting my thesis and returning to Year 5(/6) of my medical course!

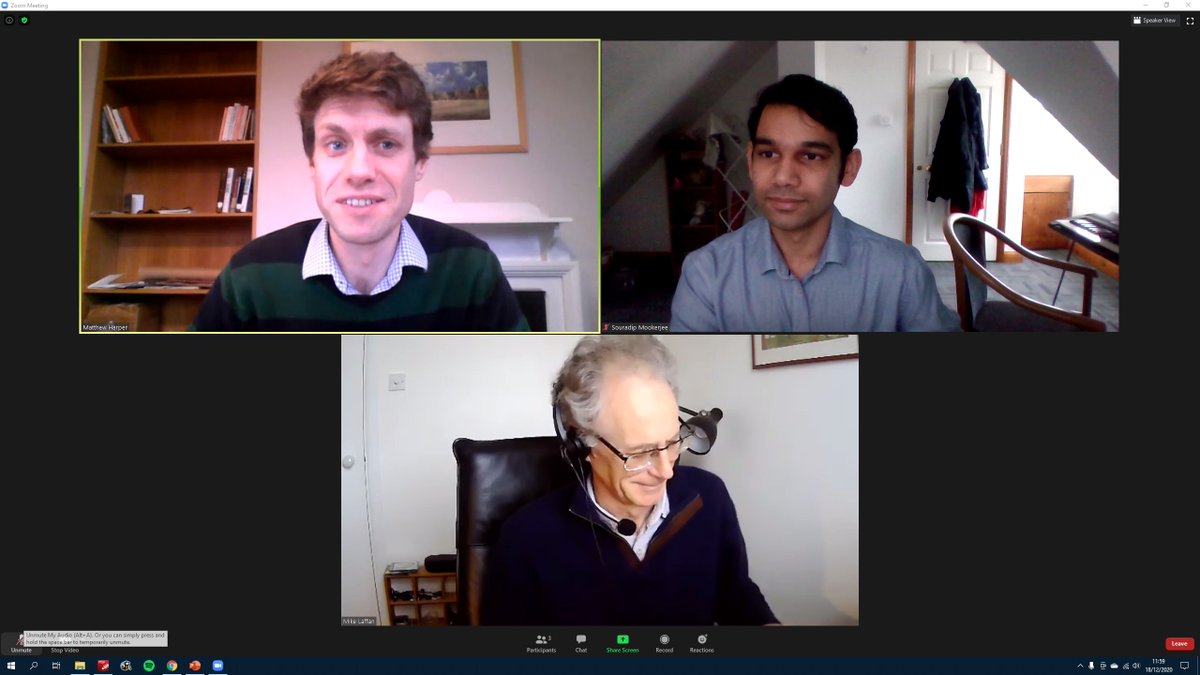

Officially a Dr? I just passed my (3hr) Zoom viva, I now have a PhD from Cambridge! #UniversityOfZoom #PhDone #MedTwitter #Science

Vaccinated

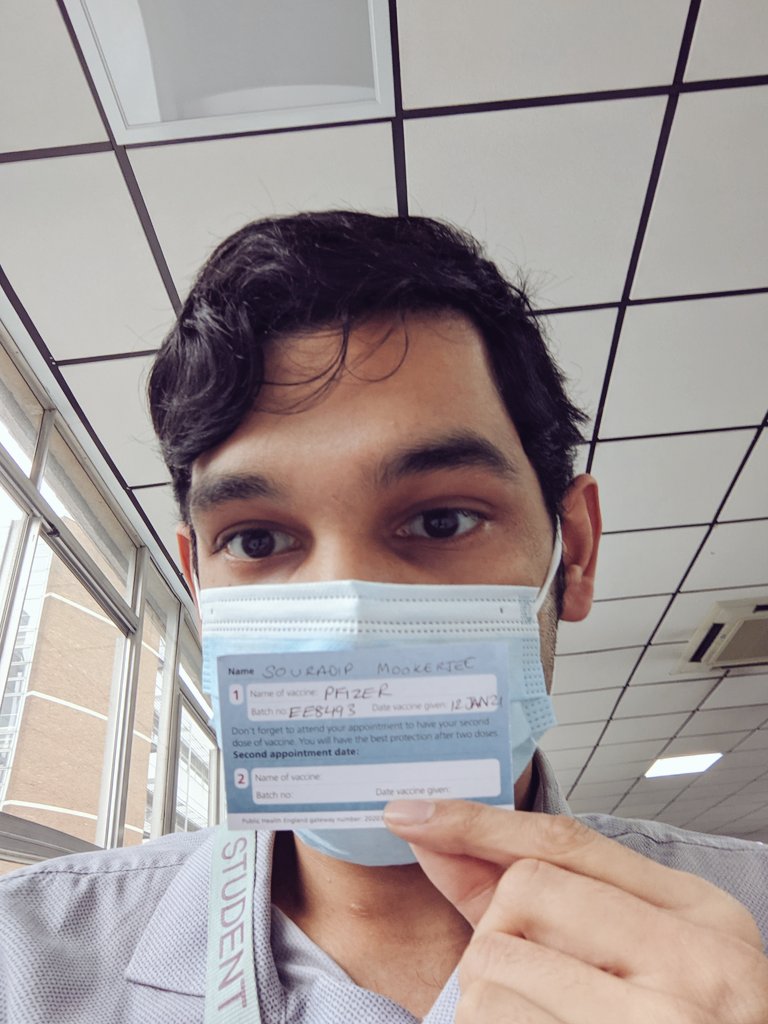

Lent term came around, with only clinical students (including vets) were allowed to return to the University, so College has felt quite empty. I did manage to get myself vaccinated (first dose), and the hospital did a great job at rolling this out and not leaving students out of the queue.

Did you even get the COVID vaccine if you didn't take a photo?? #CovidVaccine #PfizerBioNTech #COVID19 #MedStudentTwitter

The good parts

This year, the specialist medicine placements I've been on have been quite possibly the most interesting of all of medical school so far. I've had the knowledge to really make sense of all the physiology I'm seeing in action, reading the X rays, blood test results and ECGs myself and solving these puzzles. It feels like all the previous years of medical school are finally paying off!

Things that seemed impossible to understand and unconnected suddenly now snap into place, and I can see the interactions and logical connections between the mechanisms of disease and the resulting clinical picture.

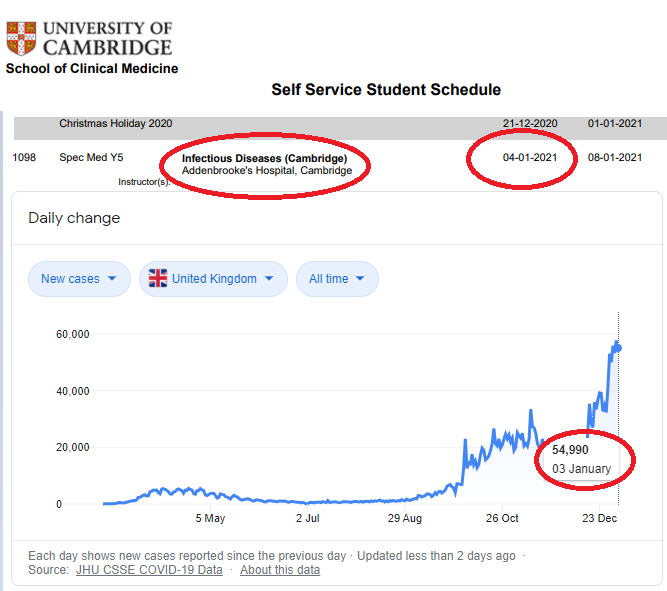

However, there was one thing that I was slightly dreading this term.

clinical medicine starter pack 2021: *gulp*

#COVID19 #Lockdown #MedTwitter #medstudenttwitter

That's right! I started on infectious diseases, and since then it's been a whistle-stop tour through everything from oncology, through to cardiology and respiratory medicine. I've been at the Royal Papworth hospital this last week and the teaching was incredibly well organised. I had the chance to see some truly cutting-edge treatments from pulmonary endarterectomies through to ECMO! I even got the chance to intubate someone under supervision before an open heart operation.

I felt like a real medical student, turning up to the wards with a friend, looking over patient notes and results, figuring out a management plan and getting taught from the junior doctors on the ward. I've also been added to the staff bank at the hospital to cover shifts because they're really struggling with having enough people to run a safe service.

My name

COVID has meant we have to wear quite strict PPE everywhere in the hospital. But in a way it feels somewhat dehumanising. It's really hard to talk with an FFP3 mask on. This has become a problem because it's hard to introduce myself as I normally would. Not only is my face covered up (and so it's easy to just become anonymous, with nobody recognising me between days, making building long-term rapport with other staff hard), but this is a conversation I've had a lot with other healthcare staff:

- "Hello, I'm Souradip and I'm a medical student here"

- "Hi, sorry, what did you say your name was?"

- "Souradip"

- "So- who?"

- "Souradip, S-O-U-R-A-D-I-P"

- "..."

- "It's like sour dip with an a in the middle" (my go-to joke to lighten the mood)

- "What?"

Not only is it hard for people to know my face, they can't even know my name! And humour doesn't seem to translate well when they can't hear half of the joke. And the best way to kill a joke is to keep repeating it again and again...

I quickly threw together an app so that I can pull out my phone to skip that conversation:

The worries and the deaths

I pulled a shift in ICU while I was at Papworth, and I attended a cardiac arrest call (someone's heart had stopped). It was on a COVID ward, so I PPE'd up and turned up. It was a man who was around the same age as my dad and also from a BAME background. I don't normally notice a patient's skin colour, but it was very apparent that there were a lot of BAME people on this ICU, especially since Cambridge isn't known for a high BAME population.

They were doing chest compressions, and the blood gases had just come back. pH of 6.9 (normal 7.35-7.45), pO2 of 5kPa (normal 11-14kPa). Not compatible with life. The X ray was just completely white where the lungs should be. He had such severe COVID that even on full ventilatory support and every drug imaginable, he wasn't able to get much oxygen into his blood through his lungs. He was so hypoxic that his heart had stopped.

They switch the person doing chest compressions routinely to make sure the person doing them doesn't get tired. They asked me to take over.

It's the first time I've done chest compressions outside of an ATLS course on a real person. A real person is warm. They have ribs that had been broken from the force of the compressions. They had a heart that I was suddenly pumping for them manually.

His heartbeat came back, but we checked his eyes with a flashlight. Not responsive to light and dilated. He was brain dead. Suddenly all the ethics and law lectures about DNACPR came back to me. I remmeber thinking at the time that how could we ever just give up and not even try to resuscitate someone? Why would we not give it our all? Suddenly it all made sense. I felt like I'd really grown up very quickly, that my perspective on it had changed. Here he was, back "alive" but not quite the same.

I listened in to the call to the family. They were desperate and bargaining and lashing out, "how could you say he's giving up? he's a fighter and he's so young, he's so healthy, he can make it through this! Why can't you put him on ECMO or something? You're not even trying!". But they had last seen him in last March. They had no idea about what was happening right there and they couldn't even come to hold his hand as he was passing away. He was peri-arrest, and his heart stopped again about ten minutes later. His lungs had not been recovering at all, and all the machines, the ECMO, were only there to support him as his body healed. It never did.

All of it was quite a harrowing experience, and I think the team of doctors, nurses and other healthcare workers handled everything the best they could. I can't think of any better way of managing the situation or a better way of breaking the bad news to the family. But it's times like that I felt quite powerless, that there was nothing that could be done.

I'm okay, although it would be weird if I didn't feel weird about the situation afterwards. I think on reflection, it's made it even clearer that medicine is the right career for me. It's those experiences that I remember when I'm studying, to remind me why I'm learning all of this stuff in the first place.